1. THE ČIURLIONIS HOUSE IN VILNIUS

Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis rented a room in this house in the autumn of 1907 when he moved to Vilnius.

read more...

Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis rented a room in this house in the autumn of 1907 when he moved to Vilnius.

Čiurlionis was already a mature, acclaimed artist and composer when he joined the Lithuanian cultural movement. He was an innovator who believed in the power of art to change the world and that community building was just as important as personal creative self-expression. During the time that he lived here, Čiurlionis conducted a Lithuanian choir, taught music, organized exhibitions and concerts and was actively involved in Lithuanian cultural life. His work fostered the vision of a creative and spiritual Lithuania.

The educational programs offered at the Čiurlionis House focus on nurturing creativity and finding connections between differing forms of artistic expression. Our wide range of programs are attended by preschoolers to senior citizens. Talented young music and art students who are just beginning their journey towards the big stage are frequent visitors in this house. Some of our exhibitions explore the environment in which Čiurlionis created and others show works that have been inspired by his creative legacy. The concerts that take place here also reflect Čiurlionis' heritage and his goal of being able to experience music as a living, constantly changing form of creativity that provides many spiritual insights.

Čiurlionis' legacy is especially relevant at our cultural evenings when we have book presentations, movie screenings and discussion panels. Our sightseeing tours in Vilnius stop at the places where Čiurlionis performed concerts and rehearsed with the Lithuanian choir and where exhibitions of his paintings took place. For those who prefer to discover Čiurlionis places in Vilnius individually, our interactive mobile app "Čiurlionis in Vilnius" is available on both main mobile platforms free of charge.

The Čiurlionis House works closely with the National Čiurlionis Cultural Route, which lets you follow in the footsteps of the artist along seven cities in Lithuania. The Čiurlionis House has played a leading role in creating cultural programs along this route.

The Čiurlionis House strives to make the name of this creative genius as widely known in the world as possible by organizing conferences, international forums, traveling art exhibits and concerts. We also host creative projects that focus on interpretations of Čiurlionis' works by internationally recognized artists.

The Čiurlionis House invites you to visit us through the words of the master himself,

"Come along with me, my friend, if you’d like to. I’m in a hurry to get to that land and along the way I will tell you some very interesting things.”

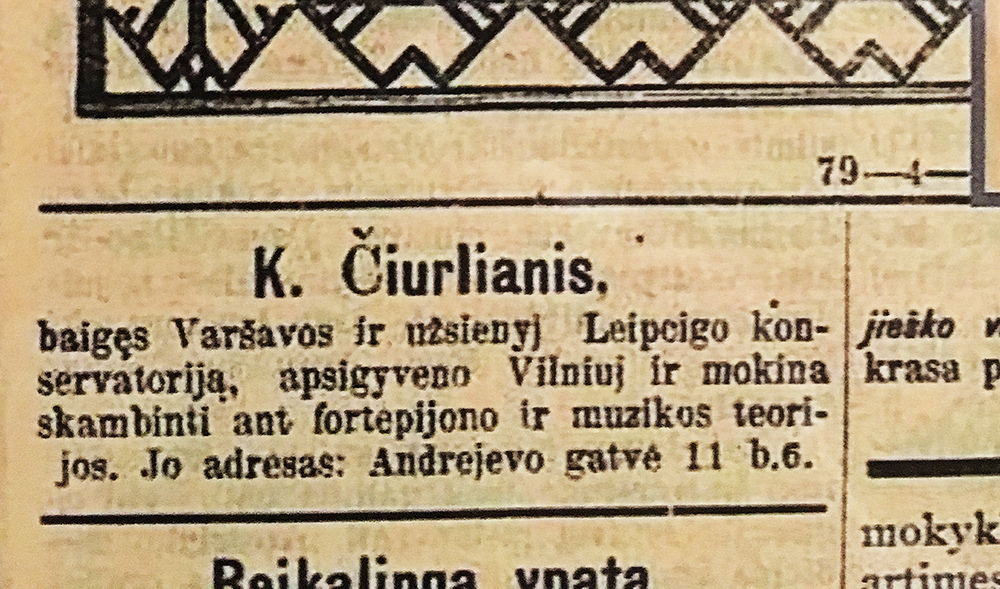

"After graduating from the Warsaw and Leipzig Conservatories, Čiurlionis has settled in Vilnius where he gives piano and music theory lessons.

His address is Andrejevo Street 11, Apt. 6." This ad was published in the Vilnius News at the beginning of 1908 and confirmed that Čiurlionis was not just visiting Vilnius but had settled here. The artist's choice to live in Vilnius was a very important event for the nascent Lithuanian movement. Everyone was curious about this highly educated and internationally recognized artist. What impression did Čiurlionis and his work leave on those who saw it at the time? How did the composer's new friends remember his little room on this street?

During Čiurlionis' first visit to Vilnius, during preparations for the first exhibition of Lithuanian artists at the Petras Vileišis Mansion, Ona Elžbieta Pleirytė-Puidienė/ Vaidilutė thus described his appearance in her diary. “Čiurlionis' paintings are extraordinary. It's hard to even describe them. I've visited a lot of European museums, but I’ve never seen anything like this. Čiurlionis himself is also extraordinary. He is one of those people who draws everyone’s gaze and forces them to notice him, but, at the same time, he is constrained by his own unique and enigmatic personality. He is of medium age and height, with a very strong, sharply defined facial profile that isn’t very appealing and rather gloomy. But his large eyes, with their deeply penetrating gaze, a calm demeanor with a clear shadow of sadness and his extraordinary intelligence set him apart from everyone else.”

This is how the artist Lev Antokolski, who will later help Čiurlionis with introductions in St. Petersburg, describes his visit, “I remember one autumn evening when I visited him in his tiny room on Andriejaus Street, where there was nothing but a piano, a pile of sheet music and some small, dry tree branches hung on the walls”. He further commented, “He was there all alone with his brilliant ideas and the sounds of his music surprised me with their empathetic sadness that were like the sharp black wings cutting across the air in his painting Longing.”

The composer Juozas Tallat-Kelpša provided more details about Čiurlionis' room in his memoirs. From him, we can get a clearer impression of the whole room, “He invited me and the next day I went to visit him. The ceiling was low, but the room was spacious. It had a narrow iron bed and a small table with a little chair next to it. His own Lippenburg brand piano had been placed along the other wall. Čiurlionis used to say that his piano was a very good one because it was sturdily constructed and was cheap - it only cost 350 rubles. A pine branch had been nailed on the wall at above the piano. Next to the bed there was another one. A few more small chairs and a suitcase containing all his worldly goods - manuscripts; a small batch of sheet music on the piano, a camera on the windowsill. Those were the entire furnishings of his room.”

Čiurlionis often seemed enigmatic and incomprehensible to his friends in the Lithuanian movement and, due to his weak knowledge of the Lithuanian language, he was reserved and somewhat unapproachable, but he was also magnetically attractive and intriguing with his extraordinary spiritual world. Each one of his creative breakthroughs, described by his colleagues, speak volumes about the extraordinary respect they had for his talent and once again confirm what an exceptional person lived in this room from 1907-1908. The writer Liudas Gira witnessed one such breakthrough and immortalized the creative atmosphere in his memoirs. “I found him sitting at the piano while his inspired hands played out his spiritual dream as if he had been imbued with power from the ancient god of Thunder and the keys of the piano were as if bewitched while he tried to express his impalpable longing. He was improvising. I asked him not to stop playing his spirit’s song. And I had that one single chance to listen to how geniuses, caught up in a mood of inspiration, create something just for themselves. It was a powerful improvisation worthy of Beethoven. Frenetic chords came up and disappeared, immediately replaced by wilder ones that were even more beautiful. It was as if the sea were being swayed by a great storm, and the melodies swayed along with it. The piano cried and wailed like an old woman from Dzūkija, sadly lamenting her only son being buried in a small hill of white sand. And so, thunder pealed once again as if all of the ancient gods had gathered to take revenge for the contempt shown for them, or as if witches were flying in at midnight for a coven at the pine tree where the man had hung himself in the forests of Dzūkija. He finished and started another one. His hands were like lightning extracting chords from all over the keyboard, giving birth to them in both major and minor keys. Soft piano melodies and loud forte ones swayed like the tops of Dzūkija’s pine trees surrounded by wind, slowly at first from afar and then suddenly shaking the whole forest with a great roar. And in that roar of sound I started to hear the peal of our sad and powerful bells that kept steadily increasing. And they pierced my heart so much it was as if the bells were resounding and vibrating right inside it."

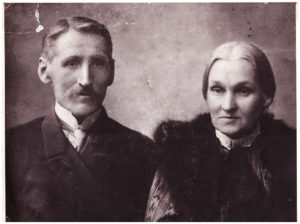

Čiurlionis' spiritual journey begins in Druskininkai where he spent his childhood, surrounded by the calm Nemunas River, old pine forests, legends and fairy tales, Lithuanian songs being sung in the amber waves of grain, the echo of a bell from a village church from afar, the chirping of birds and the whisper of the wind that will later intertwine in the magical and unique world of Čiurlionis' images and sounds that are enriched by a copious amount of symbols and metaphors.

Childhood memories, emotional attachment to his family and surrounding environment will always be like a magnet pulling the artist home. They will always serve as a source of light and harmony for him even in his darkest hours. “I feel wonderful because I just finished playing various compositions from Druskininkai on the piano. My thoughts wandered along the Pariečė road, through the potatoes and gooseberries growing in our garden, the green lawn of the church, …. I also remembered our old boat, from which we were forever draining out water. He was a witness to my many tragicomedies!” commented Čiurlionis in a letter to his friend Petras Markevičius from Leipzig where he was studying at the time.

And that’s why, wherever Čiurlionis lived, in Warsaw, or in Leipzig, Vilnius or St. Petersburg, he would return to Druskininkai at every available opportunity. He waited for those opportunities with the greatest longing and enthusiasm, and thought about them with a heart full of joy, “This is the 3rd month that I am here and there are still 7 left. As a matter of fact, that's a lot, and then ... ech! I will go to Druskininkai so full of joy that I will leave a whirlwind of dust behind me!” (Leipzig, December 17, 1901) The lines are from a letter to his mother Adele Čiurlionienė, with whom her eldest son had a special emotional attachment. His younger brothers (Povilas, Stasys, Petras and Jonas) and sisters (Marija, Juzė, Valerija and Jadvyga) also always felt their oldest brother’s undivided attention to them and his very strong support. In his letters to them from Warsaw and Leipzig their brother constantly inquired about their education and life in general. And, when he would return home from Warsaw, it was a time of joy and happy games. Maybe that's why all of the brothers and sisters learned to play the piano as they grew up, and in later years, they all went together with their brother to the drawing and painting plein airs on the banks of the Nemunas or Ratnyčėlė rivers, and sometimes even spent the night in the Raigardas Valley.

Druskininkai was always a haven of spiritual peace for Čiurlionis. Here, surrounded by his large family, he had his most beautiful hours of inspiration, his most striking creative thoughts. “You know, Zosele – I’m painting! Since Thursday I’ve been painting for 8-10 hours a day. Nothing has come of it yet but that’s fine. I’m painting a sonata (it consists of four parts and its hard going, but I’d like to finish it a soon as possible because I’m already beginning to see the second one.” Wrote the artist in a letter to his fiancée Sofija Kymantaitė from Druskininkai in Summer of 1908.

These annual "holiday" creative plein airs sometimes lasted for up to half a year. They serve as road markers for us in following the development of Čiurlionis' creative thoughts, the changes in his style and fields of interest. The works of music and art that were created in Druskininkai help us to get an idea of the stylistic development of Čiurlionis' work.

Although Čiurlionis comes to Vilnius in 1907 primarily as a painter to participate in the first exhibition of Lithuanian artists, his creative path begins with music.

Plungė, Lithuania:

When the child's extraordinary sensitivity to music began to emerge, his father taught Kastukas to play the piano when he was only five years old and by the time he turned ten, he was already substituting for his father as an organist at the Druskininkai Church. Through the intercession of a family friend, Dr. Józef Markiewicz, at the age of thirteen Čiurlionis leaves Druskininkai to continue his music studies in Plungė at an orchestral school located in the manor of Duke Mykolas Oginski. Here, the young musician fits into a particularly favorable environment. Science, technological innovations and culture were all highly valued by the Oginski family. Their manor contained an outstanding library, an extensive collection of paintings and items of great cultural value. The Oginskis family were stalwart Lithuanian patriots from the time of the Republic of Two Nations. Duke Mykolas Oginskis’ grandfather Michał Kleofas Ogiński was a well-known composer whose works are still performed today. He and his regiment also took part in the uprising of Tadeusz Kościuszko in Vilnius, after which he was forced to spend many years in exile. He spent his entire life working for the good of Lithuania.

At the manor’s orchestral school, Čiurlionis studied the basics of music, played a flute in the orchestra, and began his first creative experiments. The orchestra traveled often and for the first time in his life he saw the Baltic Sea during their annual performances at Count Tiškevičius' manor in Palanga. On important occasions, their orchestra merged with the orchestra located at Duke Bogdan Oginskis’ manor, who was Mykolas Oginskis’ brother and resided in Rietavas. It was here at Easter time in 1892, when a chandelier of a hundred lights was first lit in Lithuania at the Rietavas Church that Čiurlionis undoubtedly had the opportunity to meet the famed organist and composer Juozas Naujalis, who had just returned from his studies at the Warsaw Music Institute a few years ago.

Warsaw

In 1894, Duke Mykolas Oginskis, who has become very close to Čiurlionis and will remain his most important patron for a long time, awarded the young musician a scholarship to study at the Warsaw Music Institute. Whether by coincidence or conscious choice, he chooses to study with the same professors as Juozas Naujalis. He studies piano with one of the greatest Warsaw erudites of the time - pianist, art critic and writer Antoni Sygietynski and composition studies with Zygmunt Noskowski, who is the most famous composer, conductor and organizer of cultural events in Warsaw. Composers Mieczyslaw Karlowicz, Karol Szymanowski, Ludomir Różycki and others studied with this eminent pedagogue. Čiurlionis' closest friend, Eugeniusz Morawski, who later also turned to art, is also a student of Zygmunt Noskowski.

At the end of the nineteenth century, even though it was simply a distant outpost of Tsarist Russia, Warsaw continued to foster its memory as the capital of the Republic of Two Nations and its ambitions for becoming European cultural center. Here, the young Čiurlionis is greeted by a diverse cultural panorama dominated by the exaltation of the great legacy of Frederic Chopin and brimming with aspirations for a national revival. The young composer plunges head-first into his composition studies and into the vortex of urban culture. Čiurlionis’ compositions, especially those relating to his academic program and leisure activities, reveal not only the very serious ambitions of this student, but also his sensitivity to the environment around him. In his early compositions, we also find quite a few aural childhood experiences from Lithuania: from folk song arrangements to dreamy musical landscapes of Druskininkai. These works speak in the composer's own genuine voice, which will later evolve into Čiurlionis' unique creative world of sounds and images. The first time this powerful combination is unleashed in the symphonic poem In the Forest. Composed in 1900, it signals the beginning of the Lithuanian symphonic music [excerpt...]

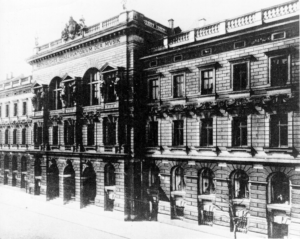

Leipzig.

In the autumn of 1901, thanks to the support of Duke Oginskis, the young composer went to Leipzig to hone his compositional skills. The city has become a magnet for young musicians from various countries. Leipzig was home to the legendary Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy School of Music and the Gewandhaus Symphony Orchestra, the centuries-old St. Thomas’ Church Boys’ Choral tradition and aura left by great composers such as Bach, Clara and Robert Schumann and Brahms, as well as world-renowned professors and composers Carl Reinecke and Salomon Jadassohn.

Čiurlionis, who did not speak German and therefore felt particularly lonely in this European cultural center, became especially close to Salomon Jadassohn, who was born in Wrocław and encouraged the aspirations of this young student from Warsaw. On the other hand, Reinecke's old-fashioned academic approach quickly became more of an obstacle for our young composer who was still searching for his true voice. Čiurlionis’ scores were already more in tune with the emerging twentieth century. And so, the Gewandhaus orchestra's concerts became a way of mastering the secrets of orchestration. He spent hours at the Peters Music Library studying and copying down the scores of Hector Berlioz and Richard Strauss. A number of Čiurlionis' symphonic ideas were born in Leipzig - the overture Kęstutis, his first symphony and a concert for cello and orchestra. Unfortunately, only the Kęstutis piano has survived. In Leipzig, Čiurlionis pushed aside his loneliness by frequently visiting the magnificent Leipzig Art Museum where he especially admired the German symbolists, especially Arnold Boecklin. During the Christmas holidays, Čiurlionis purchased colored pencils and drawing paper. Therefore, after receiving his graduation diploma in July 1902, Čiurlionis returns to Warsaw, having already decided to devote his time to both music and painting.

Beginning in Leipzig, Čiurlionis felt a growing craving for art: he pushed away his loneliness while painting. After returning to Warsaw, Čiurlionis enrolled in the Jan Kauzik School of Drawing in 1902, and in March of 1904, when the Warsaw School of Art was founded, he immediately signed up for classes.

The painter Kazimierz Stabrowski, born in historical Lithuania, near Minsk, was elected Director of the School of Art. Stabrowski was a patriot of his native country that had lost its statehood. The Warsaw School of Art, therefore, sought to continue the mission of Warsaw’s art school that had been closed after the uprising. On the other hand, after studying at the art academies of St. Petersburg and Paris, traveling extensively and becoming increasingly involved in the activities of the Polish Theosophical Society, the school’s principal and his colleagues shaped the school’s curriculum, focusing on new trends in Western art. Čiurlionis attended classes taught by Konrad Krzyżanowski, Ferdynand Ruszczyc, Karol Tichi, who all sought innovation in art. Colleagues valued Konstantinas as a musician and composer, and he often regularly won prizes for his works in the categories of applied and - especially - pure art works. As a result, he received bonuses and was even exempted from tuition fees for a year.

While In Warsaw, Čiurlionis frequented the Kryvult Salon, called the Zachenta. There he saw exhibitions of foreign and Polish artists. During his study years Čiurlionis could see the works by renowned artists from Francisco Goya, and Arnold Böcklin to Henri de Tolouse Lautrec, James Abbott McNeil Whistler, Max Klinger and Odilon Redon. He also saw works by young Polish artists here. At Zachenta, the Warsaw School of Art organized an exhibition of the work of its students, in which Čiurlionis' pieces attracted the attention of several buyers. The young artist also took part in the salons organized by Stabrowski, Ruszczyc and others, which were enlivened by many well-known young Polish writers, such as Stanisław Przybyszewski and Tadeusz Miciński, as well as editors and literary critics such as Zenon Przesmick and Artur Górski. They helped Čiurlionis to keep up with the most significant cultural developments of the time.

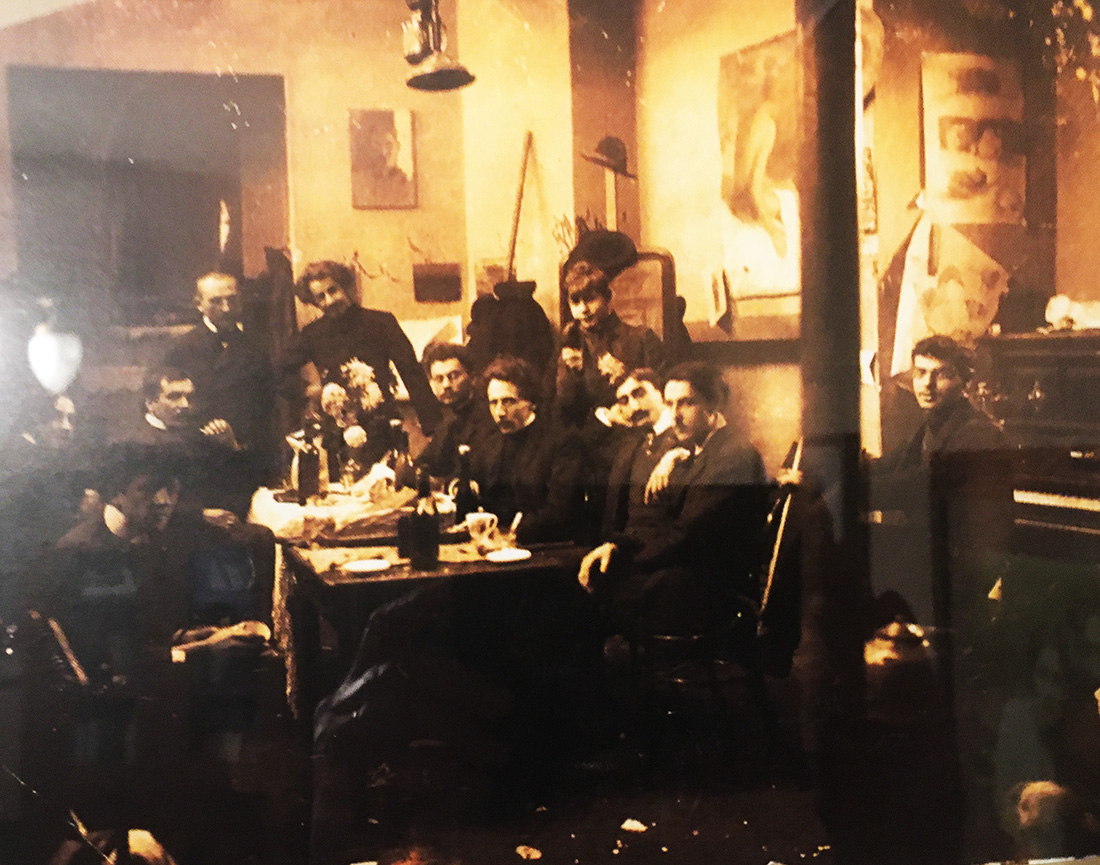

Young art students periodically gathered in a less formal environment – at Čiurlionis’ place or at some other friends’ apartments. In the photo, we see an informal gathering of colleagues from the Warsaw School of Art at the end of 1904. Fellow classmate Henryk Hayden, many years later, commented, “Do you see that piano? Very often - just like that night - Čiurlionis and Morawski would play four-hand Bach and Mozart pieces."

During the summer, the Warsaw School of Art organized plein airs. The first field trip to paint in the fresh air was organized in June-July 1904. More than thirty students, among them Čiurlionis, travelled to Arcadia - the Radvila Manor park in Nieborów near Łowicz. It was created founded at the end of the 18th century by the wife of one of Vilnius’ last high-ranking officials of Radvila family, Helena Radziwiłłowa. When Čiurlionis arrived there, some buildings were still intact: the Temple of Diana was gloriously reflected in the water of the pond, the Gothic House stood disguised in the shady area of the park and the High Priest’s Dwelling was still near the dark Rock of Sibil. Čiurlionis settled in on Poplar Island with Eugenijusz Morawski and Jan Brzeziński. They painted with small breaks from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. Only on Sundays did everyone go on outings. There were literary evenings and readings from the Chimera magazine.

After repairing the organ at the Temple of Diana, Čiurlionis and Morawski began to organize concerts in the evenings, often enhanced by singing. The masquerade ball, organized by the students, was exceptional - artists dressed in costumes envisioning "shadows of the dead". The long-gone Helena Radziwiłłowa was accompanied by Čiurlionis dressed as the historian, writer and poet Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz holding a parchment with the inscription, "Chronos will take everything away". Morawski came dressed as the green muddy Aquarius. The dance music played during the night was overpowered at dawn by loud, resonant organ chords coming from the Temple of Diana. This was how Čiurlionis and Morawski had decided to greet the rising sun! For a very long time, many of the participants vividly remembered the extraordinary atmosphere of this event and the entire plein air. In the photo, we can see the participants of the plein air, immortalized on the steps of the Temple of Diana, which is guarded by the sculpture of a Sphinx. Together with colleagues from the Warsaw School of Art, Čiurlionis also participated in a plein air in Istebna, Silesia. In addition, he also had other opportunities to travel.

Čiurlionis met this hospitable and lovely family through his classmate Bronisław Wolman while he was studying in Warsaw. He soon became a close friend of the Wolmans, and together with other fellow students he attended their salon evenings, during which discussions on the topics of literature, philosophy and music took place.

The philosopher Adam Mahrburg, who had attended Wilhelm Wundt's courses in Leipzig, was invited to present a series of lectures there. Čiurlionis visited the Wolmans more often than his colleagues: he would stop by for lunch, as he regularly gave music lessons to Bronisław's sister Halina Wolman, to whom he became tenderly attracted and later dedicated three of his piano preludes and his poetic Letters to Devdurakėlis.

The mother of the young Wolmans, Bronisława, was a true art aficionado and a highly intelligent person. She became an unabating supporter and sponsor of Čiurlionis' talent. She was also the first to find a very favorable review of Čiurlionis' works in the Russian press by the art critic Bresc-Breskovsky following the exhibition of students of the Warsaw School of Art in St. Petersburg. In the article Čiurlionis had been singled out for his unique style. And so, Mrs. Wolman immediately purchased Čiurlionis' entire series of Creation of the World. She also presented him with the most popular book among intellectuals of the time, supported his research trips, and personally invited him to join their family during their summer vacations. On his part, Čiurlionis presented her with his painting Friendship and dedicated to her his symphonic poem The Sea. When Mrs. Wolman traveled to Vilnius for the First Lithuanian Art Exhibition, she even managed to find time to talk to the bishop about the dismissal of Čiurlionis' father as a Druskininkai church organist. In a letter to his brother, Konstantinas admitted, “It is a pity that you don’t know Mrs. Wolman. She is the only amazing woman I know."

Together with the Wolman family, the artist visited the Krynica resort in the Carpathian Mountains, as well as the Anapa resort along the Black Sea. In 1905, during his Anapa journey, Čiurlionis already had his own Kodak camera. While enjoying the mountain scenery in the summertime, he photographed and painted. In a letter to his brother Povilas, Čiurlionis shared his most vivid impressions from Caucasus mountains, which became symbolic images in his work, “The shores are rocky, high, inaccessible in some places, while at others you can barely escape from the waves, and sometimes from a mountaintop you can see almost half of the sea... I saw the tops of mountains caressed by clouds and the magnificent snowy peaks with their shining crowns high above the clouds ... I saw Elbrus that was over 140 kilometers away as if it were a huge cloud of snow floating in front of a white mountain range. I saw the Darial Pass as the sun rose through fantastically wild, gray-green and pink cliffs.”

After receiving a monetary gift from Mrs. Wolman, Čiurlionis set out on a trip in 1906 through Central Europe to visit Prague, Dresden, Nuremberg, Munich, and Vienna. Main goal of his trip to attend art exhibitions, galleries and museums. While in Munich, he wrote to his patroness: "I got to see two Pinakotheks, , the International Art Exhibition, Glyptotec, and an exhibition of French artists." In addition to Munich, he emphasized the impressions that he experienced in Dresden, Nuremberg, and Prague, singling out works of Raphael, Sandro Botticelli, Albrecht Dürer, Hans Holbein, Anthon Van Dyck, Pater Paul Rubens, Titian, Rembrandt, Bartolomé Murillo, Diego Velázquez, and Arnold Böclin from the Old Masters, while Max Klinger, and Ferdinand Hodler impressed him the most from the viewed contemporary artists. He seemingly did not pay much attention to French Impressionism and Post-Impressionist art.

This trip carried great significance for Čiurlionis' own incredibly innovative experiments. This can best be seen in his series of paintings Winter, Summer, Silence, and in his pictorial sonatas that he began to paint a year later.

In the autumn of 1905, after the founding of the Lithuanian Self-Help Society in Warsaw, Čiurlionis began working on a volunteer basis with the society’s choir. Half a year later, he choir was already performing concerts.

Arrival

Vincas Palukaitis, the founder of the Lithuanian Self-Help Society, also invited Čiurlionis to adapt Lithuanian folk songs for the Vieversėlis choral songbook being prepared for Lithuanian folk schools. In a letter to his brother Povilas, sent in January 1906, Čiurlionis shared his desire to devote himself to the Lithuanian cultural cause: “Are you familiar with the Lithuanian movement? I am determined to dedicate all of my past and future works to Lithuania. We are learning the Lithuanian language and I am preparing to write a Lithuanian opera”. In the spring of the same year, Vincas Palukaitis wrote about Čiurlionis in the Lithuanian press for the first time. Towards the end of the year, Čiurlionis participated in the First Lithuanian Art Exhibition with his paintings.

Settling in

With the onset of revolutionary unrest, Čiurlionis felt increasingly unsafe in Warsaw, especially as his closest friends began to come to the attention of the police. He spent the summer of 1907 working in Druskininkai, further away from the prying eyes of the police. In the autumn, he was one of the founders of the Lithuanian Art Society. “I was at the opening of the society in Vilnius. This time I really liked being in Vilnius. It’s true that the city is very backward, but the people here are much nicer than in Warsaw. I met a few new highly cultured people and had a wonderful time. The first meeting of the society was also quite interesting. The funniest part was when the board members were being elected. I received all of the votes, and it moved me to tears because I never expected that. The final result of the meeting is that I will have to organize an exhibition in Vilnius all by myself this year, the opening must take place on December 23. Žmuidzinavičius is going to Paris, so now I will have to take care of everything alone. It’s going to be a lot of work! Very scary!". After reflection on the pros and cons of a move, the artist summed it all up in a letter to his sponsor Bronislaw Wolman, "My move to Vilnius is inevitable."

Work and Projects in Vilnius

At first, Čiurlionis began to look for private students through acquaintances, but by the end of 1907 and the beginning of the new year, he was taking out ads in the local newspaper. One of those ads reads, “After graduating from the Warsaw and Leipzig Conservatories, K. Čiurlionis settled in Vilnius and teaches piano and music theory. His address is Andrejevskaja Street 11 apt. 6”. Apparently, he only had a few students. One of them recalled how empathetic he was to the poor - reducing the cost of lessons; if you couldn’t afford a textbook, he would spend entire evenings rewriting harmony exercises by hand, so he earned very little. Čiurlionis looked for a job at a music school, but Zenon Jakubowski, the head of the institution, seemed arrogant to the musician: he had demanded a diploma of higher education. Čiurlionis, who did not attach much importance to certificates in general, impolitely shot back that he kept his graduation diplomas under his bed. And that was the end of his efforts to get a job in the music school.

Probably the most reliable source of income for the musician was compensation for his work with the “Vilniaus Kanklės” Choir. Čiurlionis held rehearsals four times a week, , but then, if he became ill, he did not receive payment for the missed rehearsal. ". We have twosided emotional connection with the choir. I teach them music theory, and at the same time I write one, two or three-voice singing exercises for them, which sometimes sound really good and I receive great satisfaction from that. But, regardless, the work is hard – there are a few talented students with good voices, but the rest belong at the bottom of the barrel as they are without an ear for music, without decent voices and without any brains. And Mr. Vileišis wants this choir to give a concert (in his opinion, it's time for the choir to sing something – what an idiot!)”.

In the small room, with its tiny window facing east, he could hardly do any painting in the dark winter months, so he made up applied art tasks for himself: exhibition posters, catalogs, book cover projects, vignettes and sketches. He wrote articles. He often sat at the piano to prepare for the lessons for his private students or the choir rehearsals, or preparing a concert program. Čiurlionis performed in the concert halls of Vilnius not only as a accompanist, but also as a soloist – his concert repertoire included works by Ludwig van Beethoven, Frederic Chopin, Stanisław Moniuszka and other composers. For his Vilnius audiences, he played several of his own preludes too and piano adaptation of the orchestra part of his cantata De Profundis.

Čiurlionis would linger at the piano for hours at a time improvising and composing his own opuses: he created the stylistically innovative series of piano landscapes the sea in Vilnius, which was later performed at a concert of Evenings of Contemporary Music in St. Petersburg.

During his time in Vilnius, Čiurlionis began developing his plans for writing opera Jūratė. He later will be developing this idea during his temporary stay in St. Petersburg.

The artist also had to participate in Lithuanian and international art meetings. He belonged to the Lithuanian Art and Vilnius Art Societies - in 1909 the Lithuanian Scientific Society invited him to participate in the work of the Lithuanian Folk Song Collection Commission. During the same year, the newly established Lithuanian Cultural Association Rūta commissioned him to paint a stage curtain that has survived to the present day.

The artist's fiancée, and later his wife Sofija Kymantaitė-Čiurlionienė, joined the Lithuanian Art Society in the autumn of 1908 and also participated in the activities of the Lithuanian Science Society. According to her, Konstantinas was "pulled to Vilnius as if by some sort of a categorical imperative to work here in the field of art, to awaken, to raise, to show people here what they can create by themselves".

Čiurlionis became involved in a debate whether to build a new National House or to buy an existing building in Vilnius for the Lithuanian cultural purposes. The idea had been developed by Dr. Jonas Basanavičius and representatives of various societies took part in the discussion, with members of the Lithuanian Art Society being one of the most active. Čiurlionis advocated the construction of an ambitiously designed building. It would accommodate concerts, a museum, exhibitions, meeting rooms, a club, a library with a reading room, rehearsal rooms and more. He promised to donate his works to the National Museum. After Čiurlionis' death, a plot of land was purchased in the Pamėnkalnis area with the funds that had been collected. Unfortunately, with the outbreak of World War I, the value of the funds completely depreciated, and the idea was never implemented.

Preparations for the Second Lithuanian Art Exhibition

Čiurlionis had the largest role in organizing the Second Lithuanian Art Exhibition. "Everything related to the exhibition had to be handled personally by myself," he wrote. “Letters - and there were many of them - articles, tickets, catalogs, posters, a printing house, the police, the governor. I dismantled the boxes with my own hands, and even carried the heaviest items up to the third floor myself while endlessly running back and forth to the frame repairman. Hanging the paintings was one of the toughest jobs. Four rooms, each will different wall coverings, light inevitably coming in from the side, huge paintings by Stabrowski. That was something! You think that everything has been exhibited well and then you see that it’s all bad. Everything needs to be dismantled once again, and this goes on endlessly. Nevertheless, at the appointed time, that is, on Thursday, February 28, at 1 p.m., everything was ready. Instead of ceremonial speeches, at exactly 1 p.m., we rolled out a gigantic blue flag outside of the building and opened the door. It was an exhilarating moment. The great majority felt like herring in a barrel, there were those who obsessively demanded explanations, there were those who, looking at my paintings, burst out in laughter, and there were perhaps only a few that felt something or understood it. Summa summarum – the general consensus was that this exhibition is better than last year’s, but it is a pity that it is smaller”. The exhibition was up until April 28. Čiurlionis participated with approximately 60 of his own works, among them the Sun and Spring sonatas, Winter series, Friendship, The Past, A Message, the triptychs Summer, My Road, Fairy Tale and others.

At the end of the summer of 1908, Čiurlionis was elected an honorary member of the society alongside the chairman Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, the director of the Warsaw School of Art Kazimierz Stabrowski and the artist and collector Tadas Daugirdas.

Before the war, the Lithuanian Art Society had organized eight Lithuanian art exhibitions, which were visited by more than 10,000 people. In the spring and early summer of 1911, the Society's members organized a posthumous exhibition of Čiurlionis’ works in Vilnius and Kaunas and assisted in organizing posthumous exhibitions of the artist's works in Moscow and St. Petersburg. The Čiurlionis Kuopa, a group of activists devoted to promote the art of Čiurlionis, initiated a permanent exhibition of Čiurlionis' works in Vilnius in 1913–1914. During the approaching front of the First World War, Vilnius lost its collection of Čiurlionis' works. They were quickly taken to Moscow and afterwards returned to Kaunas, which had become the capital of the first Independent Republic of Lithuania. The entire collection is now housed in the National Čiurlionis Art Museum in Kaunas.

In Vilnius, Čiurlionis met a young woman who became the person who was closest to him. Sofija Kymantaitė arrived in Vilnius in the autumn of 1907, after studying at the Jagiellonian University in Kraków in Women's Advanced Courses there, to work at the editorial office of the newspaper Viltis and became involved in the work of the Women's Congress and the Žiburėlis society.

This society was organizing a commemoration of Vincas Kudirka, so Sofija wrote a letter to Čiurlionis, inviting him to come to Vilnius and perform as concert at the event. Soon after, he arrived in Vilnius. After learning that he was going to be at the dress rehearsal of Gabrielius Landsbergis-Žemkalnis' play she went there with Felicija Bortkevičienė to coordinate the details of the upcoming concert. Sofija later commented in her memmoires, that when seeing Konstantinas, “Suddenly a huge wave washed over my heart. I knew absolutely everything. ‘It’s him’ I said to myself as if surrounded by a nebula while I was waiting for Bortkevičienė to bring him to me.” Čiurlionis kindly agreed to participate in the event, which took place a week later. Sofija’s words about Kudirka, imbued with romantic pathos, greatly influenced the audience. Čiurlionis performed after the intermission and afterwards sat down next to the twenty-one-year-old girl. He said, “You spoke so beautifully. While listening to you, I decided that you will teach me Lithuanian." Sofija did not object.

Čiurlionis thus described Sofija after their first acquaintance: “Miss Kymantaitė is very beautiful. She completed Baraniecki’s advanced courses in Kraków, works in the editorial office of the Viltis newspaper and speaks excellent Lithuanian. She doesn’t want to give me lessons, but that’s all right." The two would meet in her rented room three times a week. They studied the Lithuanian language from Jonas Jablonskis' textbook and also from songbooks collected by Antanas Juška, Liudvikas Rėza. They also discussed literature, music and art. Soon they became close friends and the young woman wrote articles for the press inviting more people to join the choir directed by Čiurlionis.

Shortly after the opening of the Second Lithuanian Art Exhibition, the artist invited her to this room. This is how Sofija remembered the encounter “There was a small sofa by the window with a round table in front of it, and a piano by the wall on the right. I sat down on the sofa and closed my eyes. Konstantinas improvised. How much time had passed - half an hour, an hour - I do not know. The music fell silent and twilight filled the room. In that twilight it seemed to me that the melodies were continuing to sway. I stood up - incredible joy and an endless sadness took my breath away. I got up from my place and, standing behind him, I began to stroke the back of his head and bent down to kiss his proud forehead. Without a word, he pressed my hands to his lips. It was the line that neither of us deared to cross."

The creative ideas of Konstantinas and Sofija became quickly intertwined. Čiurlionis’ songs for the choir were composed based on his fiancée’s poetry, they both collaborated on the Jūratė opera project, a series of essays jointly written by them comprised the book "In Lithuania".

Through his friendship with Sofija, the young woman whose “eyes were like the sea”, Konstantinas had the opportunity to visit her hometown of Plungė and to spend several summer months by the Baltic Sea in Palanga. These experiences greatly enhanced his creative powers. While at the seaside, he began to paint some of his most impressive cycles – The Sea Sonata, Prelude and Fugue, the triptych Fantasy. On January 1, 1909, the couple got married and left for St. Petersburg. Čiurlionis returned to Vilnius for only a few weeks in June. It was the last time that Čiurlionis was to perform in this city. He had also been commissioned to paint a stage curtain for the Rūta society. Sofija, who had already become Mrs. Čiurlionienė also contributed to the project. Čiurlionis wrote, “I painted the curtain for the Rūta Lithuanian Society. I was very happy. I stretched a 6 by 4 meter canvas on the wall, primed it myself, sketched out the contours with charcoal in two days, and then, with the help of a ladder, the painting was done on fast forward. Zosė helped me a lot in designing the flowers, and the work went squeaking forward.” After closing the door of this improvised workshop, Čiurlionis never resided in Vilnius again, although he did occasionally visit in the autumn of that year, before he left for St. Petersburg.

Konstantinui norėjosi parodysi savo darbus dailininkų sambūrių „Meno pasaulis“, „Salonas“ parodose. Jis gana greitai, nors ir ne vienbalsiai, sulaukė šių išrankių meno reformatorių pripažinimo ‒ deja, liga progresavo greičiau. Iš anuometinės Rusijos sostinės 1908-1909 metais rašyti Konstantino meilės laiškai Sofijai šiandien laikomi šio žanro palikimo „aukso fondo“ dalimi. Jie padeda geriau pažinti ne tik biografijos įvykius, bet ir be galo jautrią, grožio išsiilgusią menininko sielą.

Once he had settled in Vilnius, Čiurlionis wrote in a letter to Halina Wolman, “I want to describe in broad strokes my life here. First of all, the abundance of jobs that I was expecting here has turned out to have just been a dream. I’ve been suffering without a job from the moment that I arrived.

I have only one student who comes once a week. As a matter of fact, I recently started conducting a choir four times a week, but I’ve already managed to catch the flu three times and, if this continues, I won't make any money with the choir either."

When Čiurlionis, the director of the choir became ill, he was visited by doctor Andrius Domaševičius, who was a descendant of the left-wing nobility. As soon as Mr. Domaševičius returned to Vilnius, he joined the underground Lithuanian resistance group, the so-called "Twelve Apostles of Vilnius". He was the also the founded the Lithuanian Social Democratic Party, and helped organize the Great Seimas of Vilnius in 1905. He ran a private clinic as well as a hospital was interested in music and wrote articles for the Lithuanian press. Čiurlionis described him thus, “Dr. Domaševičius is highly intelligent, passionately in love with classical music, has dark hair and blue eyes and cared for me very attentively when I was ill.” For a while, the musician couldn't even compose - he was able to rent a piano only after the New Year. That is why he drew portraits of the people he met during that time with words, rather than with a paintbrush.

He first described a couple who were kindly disposed towards him and helped him when he was looking for ways to support hiself in Vilnius. They were Jonas and Ona Vileišis. At the time, Jonas was the chairman of the Vilnius Kanklės Society, and was one of the founders along with Čiurlionis of the Lithuanian Artist Society. Elected secretary, he seemingly didn’t have the time to manage these duties, and that is why Čiurlionis took a bit of a swipe at him in his description, “Jonas Vileišis is a very nice man who is a bit of an aristocrat, a bit bourgeois and a member of every single Lithuanian society in Vilnius, it would seem, only for the fact of belonging to it. He is very much in love with his wife”. And she was certainly someone to fall in love with: Jonas Vileišis met Ona, a beautiful girl from the aristocratic Kossakowski family, who was completely taken with her husband’s national ideals and began not only to speak, but to also to write Lithuanian. Čiurlionis played four-hand piano with her. She was warm and sincere, always ready to entertain a guest. The home of this young family somewhat filled the loss of the Wolman family’s hospitality who had remained in Warsaw.

He first described a couple who were kindly disposed towards him and helped him when he was looking for ways to support hiself in Vilnius. They were Jonas and Ona Vileišis. At the time, Jonas was the chairman of the Vilnius Kanklės Society, and was one of the founders along with Čiurlionis of the Lithuanian Artist Society. Elected secretary, he seemingly didn’t have the time to manage these duties, and that is why Čiurlionis took a bit of a swipe at him in his description, “Jonas Vileišis is a very nice man who is a bit of an aristocrat, a bit bourgeois and a member of every single Lithuanian society in Vilnius, it would seem, only for the fact of belonging to it. He is very much in love with his wife”. And she was certainly someone to fall in love with: Jonas Vileišis met Ona, a beautiful girl from the aristocratic Kossakowski family, who was completely taken with her husband’s national ideals and began not only to speak, but to also to write Lithuanian. Čiurlionis played four-hand piano with her. She was warm and sincere, always ready to entertain a guest. The home of this young family somewhat filled the loss of the Wolman family’s hospitality who had remained in Warsaw.

In his list of new acquaintances, Čiurlionis also mentioned Jonas' brother Petras Vileišis, a vocally dedicated supporter of the Lithuanian national movement. After completing his studies and becoming a railway bridge engineer, he worked as a construction contractor for structures requiring caissons in the depths of Russia and accumulated a considerable amount of wealth that he used upon his return to Lithuania not only to set up a business, but also donated to the first Lithuanian daily, Vilnius News, to a Lithuanian printing house and a bookstore. Many of the nation's most enlightened people, such as Jonas Basanavičius, Gabrielė Petkevičaitė-Bitė, Mykolas and Vaclovas Biržiška and Juozas Tumas-Vaižgantas who organized the Great Seimas of Vilnius, had been able to set up residence in Vilnius in 1905 thanks to jobs provided by Petras Vileišis. The first Lithuanian art show was held at his mansion and Lithuanians were able to view Čiurlionis’ works for the first time. He was a member of the Vilnius City Council for four years.

In this room you can see photos from the First Lithuanian Art Exposition at the Vileišis Manor. "Petras Vileišis is a very sympathetic old man, simple, kind-hearted," was the way that the artist described him, adding, "a few years ago he had about 500 thousand, and now he has been left with 50. He gave it all away to people and for various programs for the rebirth of the nation." In fact, Vileišis' funds dropped even more dramatically, and this prompted him to leave for Russia again to earn money. In the letter, Čiurlionis admitted, "We sympathize with each other."

While hanging his paintings for his first exhibition, Čiurlionis became acquainted with the twenty-seven-year-old artist Petras Rimša, who was one of the first in the press to Lithuanian artists to think about a joint exhibition of their work. At the beginning, Rimša, who had come to Vilnius from a rural environment, was a bit shy around his older colleague, but soon became close friends with him and became a dedicated assistant when Čiurlionis was organizing the Second Lithuanian Art Exhibition. Later, Rimša recalled with pleasure what a good mood had prevailed when the artists hung the First Lithuanian Art Exhibition. “Of course, the soul of the good mood in our circle was Antanas Žmuidzinavičius. But Čiurlionis was also a part of it. They were both also wonderful at singing while preparing the exhibition. After all, it’s natural to work while singing. It seems like today that I see Čiurlionis and Žmuidzinavičius up high on ladders and hanging paintings. And then a wonderful song from Dzūkija starts to pour out of their young hearts, "Oh, the woods, the woods..." We would get so involved in the singing that work stopped altogether. The preparation of the exhibition cemented the artists into a very close friendship that was quite rare.”

In September of 1907, the landscape artist Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, who had studied in Warsaw and Paris, became the chairman of the newly established Lithuanian Art Society. He remained in this position throughout the life of the society. When in 1908 he set out to further his studies in Munich and raise funds for the society for travel to America, Čiurlionis replaced the chairman in all of the organizational work. Žmuidzinavičius remembered how, at the opening of the First Exhibition, Konstantinas came in all dressed up with an oversized bow tie. There was one young lady, who upon seeing his strange paintings in which "the underground mingled with the sky", decided that she wanted to see the artist himself, whom she thought would probably “look like God knows what.” And Čiurlionis, who was standing nearby, was quick with an answer, "Madam, he's truly horrible: like a dragon who swallows virgins." Žmuidzinavičius, who loved concerts, continued on for a long while about what an impression Konstantinas’ music made on him, "When Čiurlionis would play, life in this world came to an end: the artist himself would transcend this world and take his listeners along with him to other more beautiful worlds of dreams and mirages."

After moving to Vilnius, Čiurlionis stayed in close contact not only with Lithuanian artists. One of his most important acquaintances was with a contemporary artist Lev (Leiba) Antokolskis. After he graduated from the Vilnius School of Drawing and studied with Ilya Repin at the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, he spent a bit of time in Paris. For the past five years, he had already been the director of drawing classes at the Vilnius Jewish Crafts School in Vilnius. The school had been initiated by the Society of Industrial Arts, which a year ago had bestowed the institution with the name of Lev's uncle, the famous sculptor Mark (Marduch) Antokolskis. Čiurlionis' vivid imagination first caught the artist's attention when he visited the First Lithuanian Exhibition. His symbolic works immediately appeared to be "full of deep philosophical meaning," and he equated the original interpretation of musical themes to a "shining, dazzling meteor." Later, Čiurlionis met with Lev Antokolskis on organizational matters at the Vilnius Art Society. The artist's acquaintance with representatives of the Art World in St. Petersburg proved to be very useful for Čiurlionis in establishing business relations in the then capital of tsarist Russia. After Konstantinas’ death, Antokolskis remembered how he loved the crooked streets of Vilnius. “I remember one autumn evening when I visited his little room on Andrejaus Street where there was nothing but a piano, a bunch of handwritten music scores and dried out autumn branches hanging on the walls. He was there alone with his ingenious ideas and the sound of his music surprised one with its grief...” In this modest home, conversations were often extended through music by fingers running along the Lippenberg piano’s keyboard.

Čiurlionis was also visited in his room by Ivan Trutnev, a painter of religious and folk scenes and portraits in the academic tradition, who was already eighty years old at the time. After studying in Moscow and then touring the cities of France, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands and Italy, he worked in Vitebsk, and for the past four decades headed a drawing school in Vilnius. He had earned the title of Academician of the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts, as well as the titles of State Counselor and True State Counselor. Among the works of Ivan Trutnev was a project for a monument to the “Hangman of Vilnius” Mikhail Muravyov, but Čiurlionis may not have known about it.

At the end of 1908, Ferdynand Ruszczyc, who had taught painting to Čiurlionis at the Warsaw School of Art and had somewhat influenced him, moved to Vilnius. They were both artists of virtually the same generation as they were born only 5 years apart. After having studied in St. Petersburg, traveling to Munich, Berlin, Dresden, Paris, Vienna, and working at the Krakow Academy of Arts in for a year, Vilnius attracted Ruszczyc because of its less pretentious environment, and because an early exhibition of his works had taken place in this city. The house in Užupis where Ruszczyc lived was relatively close to Čiurlionis' rented apartment and the two artists would occasionally meet. Once, when Ruszczyc visited the Lithuanian Art Exhibition, he commented that only Čiurlionis’ works were worthy of note. Although Ruszczyc liked the Scherzo from Sonata and the entire Zodiac series, he couldn’t refrain from reproaching the artist for too much Kabbalism and too little actual painting in his work.

After the death of Čiurlionis, Ruszczyc, who was one of the bearers of his coffin and gave a eulogy at the gravesite, focused on his essential impression of Konstantinas. “We have gathered to say goodbye to a person of unadulterated purity, to a friend with noble aspirations, and will remember him deep in our thoughts as a tragically interrupted song. He left us for other worlds, about which he dreamed during his such short life, to that distant country, with which we are not familiar, but we know of it, we are it and feel it inside of us. Čiurlionis is building bridges of colors and sounds from our shore. To others, Čiurlionis was an expression of that dual homeland from which arise both the artist and the man - a homeland with one great Spirit, which, regardless of age or nationality, unites our souls into one great community. And the others are our own lands, against which her son nestles with love. There is one painting by Čiurlionis, well known to you. A bird emerges from the breaking dawn, passing by the peaks of mountains with the wide flutter of its wings, quickly flying away into the distance. This is The Message. That was Čiurlionis’ message. He was the harbinger of new, young art, on which he left his own mark. And he proclaimed to his land and to his countrymen the beauty of the spring that was awakening in them. And so, he left us in the spring."

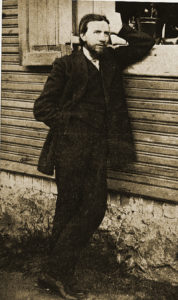

Another artistic soul close to the environment of the Vilnius Art Society was Stanisław Filiber(t)as Fleury. After graduating from the Vilnius School of Drawing and learning the secrets of the craft of photography in the workshops of several famous masters, he decided to establish his own photo studio. He liked not only photographing the images of Vilnius, but also painting the landscapes of this city and illustrating some books. Later on, he was one of the first to begin producing stereoscopic photographs in Vilnius. When Čiurlionis arrived here, he had been working in his studio on Didžioji Street for close to two decades. Because the studio was very close to Konstantinas’ rented apartment, he dropped by his colleague’s place on the morning of June 1908 to have his picture taken. His fiancée Sofija Kymantaitė said that the photo was taken after they had both spent the night together on Gediminas Hill. “That morning, without practically any sleep, after having transported a piano and being dead tired, he remembered that he had promised a photo to Šaltinis. He stepped into the photographer’s studio and the result is the photo that everyone has seen. But, in that photo there is something that has died - there is no clarity in his expression, no matter how gray the face – the constant glow of his eyes is missing.” ‘I was so tired that I didn't even comb my hair’, he tried explaining afterwards." You can see the photograph hanging on the wall in this room.

Antanas Vileišis, an active participant in the Great Seimas and the Science Society, also worked in the organizing committee of the First Lithuanian Art Exhibition. Being a progressive left-wing man, the doctor was sincere in his efforts to found societies for his socially vulnerable countrymen and also worked in the Vilnius City Duma. Čiurlionis conducted some of the choir's rehearsals at the premises of the Vilnius Lithuanian Mutual Relief Society, and Antanas Vileišis was the chairman of this society.

Konstantinas was visited in his home by the writer Liudas Gira from Dzūkija, who wrote poetry and contributed his writings to many periodicals. The composer had asked him to translate a song for which he had composed music from Polish into Lithuanian. His musical improvisations evoked a string of romantic images in the soul of the twenty-four-year-old. “His hands, like lightning, evoked chords from all over the keyboard. Piano and forte melodies swayed like the tops of Dzūkija’s pines, swinging in the wind,” was the way Gira described the work, which, as far as the writer remembers, the composer called Bells. At that time, the composer spoke about the importance of dissonance, which one can also hear in Lithuanian multi-part songs. Perhaps their mutual interest in folk songs and folk art connected them, because when Čiurlionis started painting sonatas, Gira wrote in the press that he regretted the vagueness of this type of theme, preferring "fairy tales".

Čiurlionis had a number of rehearsals and concerts with the St. Petersburg Conservatory vocal class student Kipras Petrauskas, who became well known to the Lithuanian public after his performance in the melodrama Birutė where he played the part of Birutė's brother. It is not known whether Čiurlionis was acquainted with the first composer of a Lithuanian opera Mikas Petrauskas, but there is no doubt that he met with the author of the libretto Gabrielius Landsbergis-Žemkalnis.

Marija Piaseckaitė-Šlapelienė, who played the main role in this melodrama, also sang in the choir led by Čiurlionis. Rehearsals took place quite late - after a day's work was done. For over a year, Marija had been managing a Lithuanian bookstore that she had opened, while at the same time raising her young first-born daughter, so she decided not to pursue a career as a vocalist. However, singing in the choir helped her to nurture her hobby. On dark winter evenings, Čiurlionis often had to accompany his choir member until she returned to her home on Saracėnų Street.

During preparations for the Second Lithuanian Art Exhibition, Čiurlionis was earnestly assisted by several loyal helpers of the society - Sofija Gimbutaitė, who came from Lithuanian nobility and had acquired the profession of a dentist in Paris and Marija Putvinskytė. Together with Čiurlionis, Sofija Gimbutaitė joined the board of the Lithuanian Art Society, was the organization's treasurer and later served as a secretary. She sincerely believed that a necessary condition for the survival of the culture of every nation was the development of art as well as the establishment of a national museum and contributed as much as possible to the realization of this goal. Sofija donated a huge amount to the society and this ensured her membership in the organization for life. The headquarters of the Society were registered at the address of her apartment on the former Preobrazhenskaya Street. Letters and the works of professional artists as well as folk artists who intended to participate in the exhibition were sent here. From there, Konstantinas carried them to framers, and later to the premises rented for the exhibition. She not only fixed the teeth of needy artists for free, but also allowed them to spend the night in her office, "lending" them money free of charge. Čiurlionis had also used these same services more than once. In the autumn of 1907, he stayed with Gimbutaitė until he found a room for rent on Andrejevskaya Street – where we are right now. Even when he moved out, he went to this caring woman every day for lunch. Sometimes, when he was too busy, she brought lunch to the artist at his rented place. “She is an incredible creation. She brought me borscht today and warmed it up on the small stovetop. I lunch at her place and she has started to fix my teeth," admitted Konstantinas. Unable to pay for lunch, the artist presented Gimbutaitė with his green-colored painting Boat. Gimbutaitė had also acquired the first part of Čiurlionis' diptych Sadness. Before her death in October of 1911 she bequeathed both paintings to the Lithuanian Art Society.

Patrons of the Art Society would also gather in Marija Putvinskytė's apartment. After arriving in Vilnius in the summer of 1906, Marija opened her dental office there and became actively involved in the preparations for the first Lithuanian art exhibition. She participated in the founding and board meetings of the Lithuanian Art Society and assisted many societies. Marija was close friends with Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, and when he went abroad, she assisted Konstantinas in organizing the exhibition. While on duty in the halls and at the cash register, she remembered how visitors reacted to symbolic art. When an alleged art connoisseur pointed to a painting by Čiurlionis and asked out loud, "A to jaki wariat namalował?", he was unflustered and replied, “A to ja” to the laughter of bystanders. In his letter to Marija, the artist described her as “an enthusiast. She's nice and plays billiards." After getting to know her better, he experienced how kind and generous she was. When he had to go to Warsaw to print the exhibition posters, it was Marija who provided him with train tickets.

The journalist and writer Ona Pleirytė, who had recently married Kazimieras Puida, a great fan of literature, exhibited an exceptional amount of exalted attention to Čiurlionis. They both worked in the editorial office of the daily Vilniaus Žinios. Puida, who helped to organize the First Lithuanian Art Exhibition, had even held the position of managing editor for a while. However, the marriage of these young people was in crisis and so, the woman began to look around for a man who was her soulmate. She often showed up at Čiurlionis’ side, wrote pieces based on the motifs in his paintings and published her impressions under the pseudonym of “Vaidilutė”. In gratitude for her attention, the artist presented her with his painting Longing, which was destroyed during the disasters of World War II. She has described the artist and his works quite accurately. “Čiurlionis' paintings are extraordinary. I have visited many European museums, but I have yet to see anything like them. Čiurlionis himself is also extraordinary. He is one of those people who draws everyone’s gaze and forces them to notice him, but, at the same time, he is constrained by his own unique and abstruse personality. He is of medium age and height, with a very strong, sharply defined facial profile that isn’t very appealing and rather gloomy. But his large eyes, with their deeply penetrating gaze, a calm demeanor with a clear shadow of sadness and his extraordinary intelligence set him apart from everyone else.”

"These are all of the participants in the comedy or drama in which I have to live," is how Čiurlionis laughingly introduced the people he had met in Vilnius.